“The depiction of Brad Raffensperger as if he’s the people’s champion … is rather laughable for those of us here in the state of Georgia who have watched Brad Raffensperger over this cycle alone actively engage in behaviors that undermine the election process,” Changa said. Changa criticized Democrats for praising Republican politicians such as Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger for standing up against President Donald Trump’s false election fraud claims.

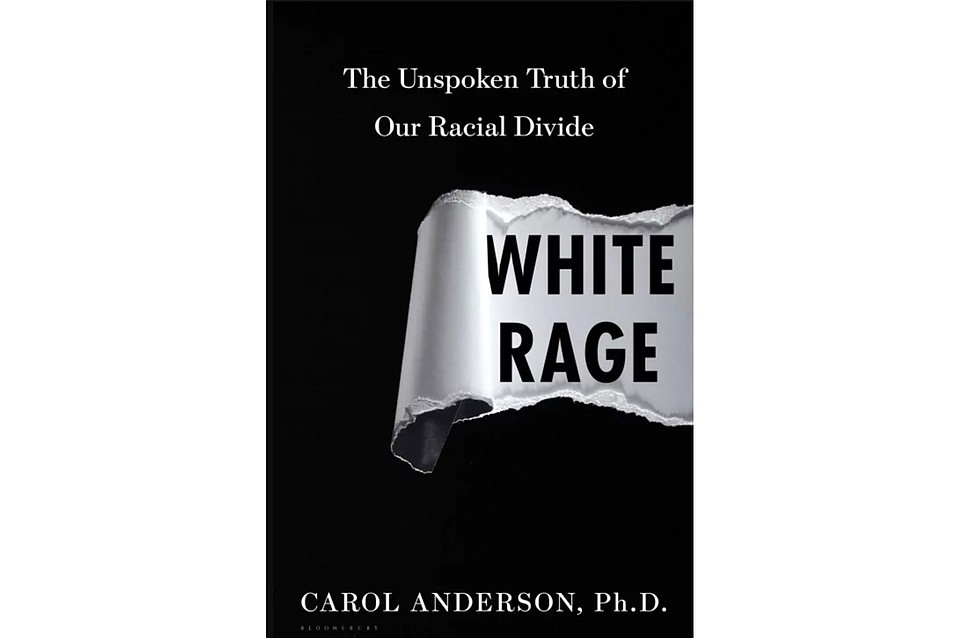

“That rage then comes up in terms of these policies … they then also sanction, approve the violence that reigns down on Black people.”Īnoa Changa, a freelance reporter covering reproductive justice, and Joe Lowndes, a professor of political science at the University of Oregon, were also panelists. “When you see the kind mobilization and organizing that is happening in the Black community to gain hold of their rights, it is enraging,” Anderson said. This is why we have massive resistance after Brown, the war on drugs after the Civil Rights Movement, Donald Trump after Barack Obama.”Īnderson said that rage felt by white supremacists is rooted in the lie that Black people are not citizens and do not have rights that white men are “bound to respect.” “This is why we have Black codes after the Civil War. “We often think about white rage as the kind of violence that we see, but white rage when I’m talking about it are the policies that are put in place to undermine, undercut Black advancement toward their citizenship rights,” Anderson said. While the attack on the Capitol demonstrated “white rage,” she said the phenomenon applies to more insidious infringements on Black individuals’ rights. Anderson created the term in a 2014 op-ed in response to the killing of Michael Brown, and she advanced the concept in her New York Times Bestseller book, “White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide.”

“White rage” is the idea that racist structures have created white bitterness toward Black people. “At one moment we were celebrating the historic electoral wins in Georgia, and at the same time we were bracing for the existential threat to democracy that was coming from the Capitol,” Crenshaw said. 6 and the implications it has for the country. Crenshaw said she felt compelled to host the talk to address the tension of Jan. (The Emory Wheel)ĪAPF Co-founder and Executive Director Kimberlé Crenshaw, a legal scholar known for coining the term “ intersectionality ” in 1989, moderated the event. Carol Anderson explains how white rage contributed to the Jan.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)